|

|

|

Editing Double-System Sound material

|

March, 2003

Editing

Double-System Sound material

A suggested workflow in FCP

By Phil

Ashby

Double-system

sound (or separate sound as it's known in the UK) shooting, although

unusual for video production, is the norm for location filming,

and certainly in the days of 16mm film was the standard route

for TV productions. The technical quality of the sound recording

on professional video camcorders can be very good (although on

some prosumer units it is middling, to say the least), but most

sound recordists, given the chance, prefer the flexibility and

control they have with their own separate recorder (be it DAT,

mini-disc or even analog tape). Camera operators too can appreciate

losing the umbilical connexion to the sound mixer, or the need

to worry about the radio mic links.

You may have spotted the assumption

here, that there is indeed a 'sound recordist' - so we are talking

about shoots with a 'crew' and not a person.

There is a price to pay for this

flexibility, and it comes when the material is being edited;

there's more of it, and first off, the sound tracks have to be

married to the video tracks. There's an extra headache - this

relationship needs to be kept track of throughout the edit.

How do you do that with FCP? I'm

not claiming this is the only way to do the job, nor even the

best, but it's a system that has worked for me, fairly reliably.

First off, it's worth repeating

that double-system sound involves a deal of extra work in post-production,

and you need to budget the time for this. But you probably know

that already if you've opted to work this way, and have balanced

it against the aforesaid flexibility. In our case, the sound

quality on the camera we then operated (Sony PD100) wasn't up

to the production standard we required on a project, and we decided

to record sound with the HHB Portadisc (which we use for other

sound-only projects). This is a professional quality Minidisc

recorder, with two sound inputs and the ability to transfer digitally

to the Mac through the USB port. Note there is NO time-code (SMPTE

style) on this system, but the MD does record a time of day (minutes

and seconds) and number each track: sufficent for identification,

but not enough to lipsync with! So syncing is done the old-fashioned

manual way; however the stability of the MD recording is such

that we found no loss of sync against the video over 10 minute

takes.

A couple of routines helped to

keep the editing flow smooth:

Shooting:

We recorded a safety (syncup) track on the camera, from the internal

mic. Portadisc and camera real-time clocks were adjusted to match

at the beginning of every day - they would drift apart by about

a minute in a couple of days. This was to aid identification

later, as a check on the logs we kept. We didn't put slates (clapper-boards)

on shots, but used finger clicks or louder hand-claps, identifying

MD track number on sound.

As it happened, I was using the

Photo/JPEG codec to capture the video clips in FCP for the rough

edit - which meant a full-resolution recapture would be needed

later on. If you don't shoot clapper-boards, the quality of the

pictures might not be good enough for syncing if you don't have

a camera sound-track reference.

Capture into the Mac:

Video was treated as usual, batch captured from DV.

The MiniDisc sound was captured

through the USB lead, using 'Capture Now' in FCP. There's a Mac

OS problem here (using OS 9). Effectively you're using the Mac's

Audio mixer app to select the USB line input. I found the system

could become unstable unless I did this before running FCP. The

snag is that this will mute the Mac's internal speakers, making

monitoring difficult. The easiest work-round (we have a Folio

audio mixer hooked in to the Mac for monitoring) was to plug

the MD's analog output to the tape monitoring input of the sound

deck, and listen to that.

The Mac

Audio Control panel, with USB line in selected. Switch the MD

on and plug it in before selecting. Do this before running FCP. |

It's true to say I find the Mac to be

somewhat cranky about USB devices. As with firewire, I prefer

to put the AV device on its own port at the back of the Mac,

and chain all the other devices (keyboard, graphic tablet, shuttle

controller) off the second port. Often I find a deal of unplugging

and replugging is required before all devices are happily co-habiting

with the Portadisc. Maybe it's just an OS9 habit? Whatever, it's

important to check the system is happy and stable before running

FCP.

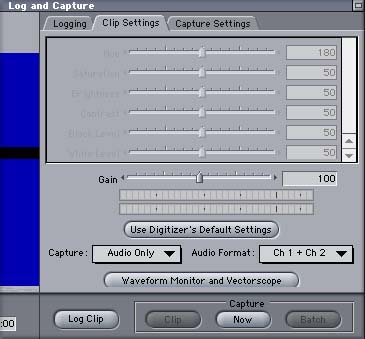

The workflow for capturing sound from

the MD was:

1.

Configure Lwith USB line input, non-controlled device. It'll

be 44k sampling, using the internal Mac hardware, which matched

the Portadisc. Clip settings Audio only 1+2, no video!

Log and

Capture window, control settings |

Log and

Capture window, clip capture settings |

2.

Configure Portadisc to play 1 track at a time (it'll pause at

the end of each track, and gives a countdown too - 'track' here

meaning a stereo take, not a timeline track). This isn't essential,

given it's 'capture now' under manual control, but it is easier

to keep the sound in separate clips corresponding to separate

takes.

3.

Hit play on the MD, click on capture now. When finished, don't

forget to save tracks in a folder marked 'MDs for XXProject 44k'

or whatever, on the capture scratch disc.

4.

Whilst capturing in real time, amend/write sound log to identify

which tracks correspond to which day/time. (Afterwards, type

the information in to the notes column for the sound clip, and

for belt-and-braces, add this to the info for the matching video

clip.)

Then, after capturing, convert all tracks

to 48k sampling, and store in a separate folder. I used QT to

do this, outside of FCP. I figured this would save a lot of hassle

in FCP, working with 'wrong' sampling freq. (Our cam is DVCAM,

48k as are clips, and sequences).

For reassurance, I also copied all the

clips (48k) onto a CDR. These audio clips have become the primary

source, and it'll always be possible to 'recapture' by copying

the QT audio file back into the Mac from the CDR. It's quicker

and more repeatable than re-transferring the MD tracks.

Finally, in FCP, import all 48k clips

into a bin. Ours were named in the pattern 'MD_tk11_48k' where

tk11 means take 11. This information is what will appear in the

timeline as well as in the bins, and will be referred to frequently.

Pre-editing of clips:

Ours was a documentary project, not quite A roll interview/B

roll cutaways, but certainly split neatly into one programme

section per location. I made up sync clips for each shoot, by

editing video clips and (camera) sound into a sequence., then

editing the MD clip to another sound track..

Syncing I found straightforward - the

method I use is to rough-sync by cueing ins and outs for the

edit of the MD clip onto the audio track. Then I adjust by eye

with waveforms turned on in the time line, and finally adjust

by ear. With both sound tracks playing, and the MD track selected,

use the < and > keys to change its position a frame at

a time until the echo is gone. You do need to be fairly close

in sync to begin with, and have the levels roughly equal. It

is possible to make adjustments in increments of less than a

frame, by fine adjustment of the in point on the audio track,

but I didn't find this necessary for lip-sync in the first place.

Purists may disagree, but there's a trade-off between perfection

and time taken here. (And moving by increments of a frame is

all that's available to the film editor.)

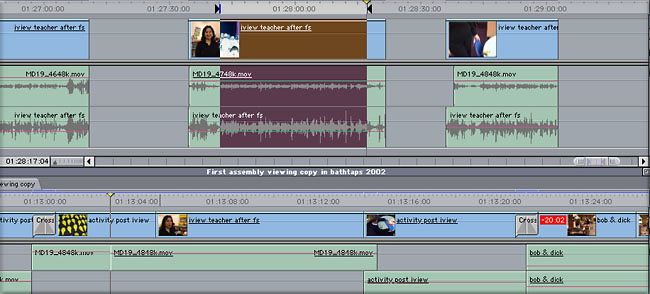

Sequence

of sync'd up clips. Audio track 1 is the MiniDisc sound, imported

as an audio file. Audio track 2 is the camera mic sound. Near

the end of the clip you can see the obvious match of the two

tracks. The camera audio track was on auto level and is -very-

high level. The MD was recorded to a more conservative setting

to avoid distortions on peaks. Waveforms have been toggled ON

to show the match. Thumbnails are also ON for the sake of the

screen grab. |

Once I'd found sync, I moved the MD sound

up to Audio track 1, leaving track 2 as a reference.

Select and Link each clip to bolt the

sync down between the video and audio tracks, and when you've

finished, Duplicate the sequence in the browser and rename the

Copy 'Safety' or whatever. In this work pattern, the sequence

of sync'd clips becomes the play-in material, and it's well worth

having a fallback of the original before you start messing around

with it in the Viewer!

Clip as before

in the sync sequence, now the tracks have been locked - the names

are underlined to show this. Clip as before

in the sync sequence, now the tracks have been locked - the names

are underlined to show this. |

At this stage, one workflow (which was

mentioned in a recent Apple article) would be to burn a DVD or

clone these sequences off to a DV tape, and treat them as raw

material for editing, but it's not essential.

Program Assembly:

I tried several methods of building the program itself from the

sync'd clips, and some gave me problems either when I tried to

recapture, or with interpreting the clips on the timeline (using

subclips for instance.).

The method I found that gave least trouble

later is as follows:

The source material is the sync'd sequence,

accessed from its timeline. That is edited into another timeline

to make the program sequence. I use two monitors hooked up to

the Mac. The right hand screen contains just the timeline views,

with the two timeline windows one above the other.

Here's the important action in the workflow,

marking up the shot.

Mark IN and OUT on the source timeline,

then Opt-A to make this a selection, Apple-C to copy, then, in

the program sequence, Apple-V to paste (at the position of the

playhead). Pasting takes note of target tracks, and preserves

the stacking of the clips that are pasted, but beware -it will

overwrite any other material. It's safest done onto wide open

spaces as you first assemble.

The upper timeline

is the source sync'd clip, with IN and OUT marked, and the area

selected ready for copy/pasting. The lower timeline is the program

assembly. This screengrab was taken some time after the assembly

was done to show the layout. I do not advise pasting into a full

sequence such as illustrated here, without a deal of experience! The upper timeline

is the source sync'd clip, with IN and OUT marked, and the area

selected ready for copy/pasting. The lower timeline is the program

assembly. This screengrab was taken some time after the assembly

was done to show the layout. I do not advise pasting into a full

sequence such as illustrated here, without a deal of experience! |

The big advantage of pasting clips this

way is that it preserves the names of the MD and video clips

in the program timeline.

I don't recommend using the sync'd clips

in the Viewer and editing as inserts or overwrites from there,

nor making subclips from the sync'd clips and using these subclips

as playin material. Both these methods can lead to nesting of

nests - bad news for recaptures, I found in previous trials.

I'm not saying they definitely don't work, but problems are just

that much more difficult to unravel when your main sequence doesn't

show the primary clips and soundtracks in the timeline.

As you'll maybe have noticed from the

screenshots of the timelines, I played safe and kept one track

of the original camera sound in the 'sync' sequences, so I always

had a reference to playback against the MD sound. It's not absolutely

necessary - provided you ensure that you mark the video and audio

tracks 'in sync' and lock them together for each clip that you

sync up.

One tip that will save a lot of time

is to keep to a discipline with your use of audio tracks - for

instance, keeping all MD clips on 1, camera sound on 2 (or further

down to keep out of the way), narration on 3 - or more if you

are making a stereo mix, of course.

Once you've laid the clips in, you can

close the source timeline, and trim edits in the program sequence

in the conventional way. Because you've pasted this sequence

from original clips, you're as free as ever to trim, extend,

and overlap clips.

If you do keep the original camera tracks

in the assembly of the program, don't forget to mute them (or

delete) before mixing down!

copyright © Phil

Ashby 2003

Phil

Ashby is producer / editor for

production company Bright Filament, who specialise in science/technology

and education based programmes in all electronic formats known

to man and woman. His biggest fears for the future are that one

day Apple will perfect FCP and there will be no problems left

to solve, the accumulated weight of manuals will overstress the

structure of his house and that render times will shrink to negative

numbers, thus increasing the working day.

This article first appeared on www.kenstone.net and is reprinted here

with permission.

All screen captures and

textual references are the property and trademark of their creators/owners/publishers.

|