The hardware

Photos and photo-motion are an

essential part of films, especially documentary productions,

and the lowly flatbed scanner has taken on a new life as a major

tool in digitizing stills for use in digital video. Today's inexpensive

scanners offer incredible resolution. Scanners sporting 1200

dots per inch (DPI) optical resolution-- that is, not

invented or "enhanced" in software but actual tiny

"pixel-picker-uppers" mounted in the scanning tube--

are now easy to find among Canon, Microtek, Hewlett-Packard and

other manufacturers. One of my favorites as of this writing is

the Canon LiDE 30. Retailing for US$100.00, it's slim, storable,

and among the first without a power brick-- totally USB-powered.

I'm sure others will follow.

All scanners listed above supply a plug-in

for direct Photoshop acquisition/import. Most all inexpensive

scanners offer an 8 1/2" X 11" scanning bed. Scan oversized

images in tiled sections, and join them in Photoshop, and-- very

important-- scan each tile at the recommended dots-per-inch

(DPI) rate determined for the total width. Proper dpi rates are

discussed below.

Hardware includes megapixel digital cameras

from Nikon, Olympus, Canon, et al. Many have USB connections;

you can take a high-pixel picture, download it through iPhoto/Image

Capture, and process it further for import to Final Cut Pro,

and still be able to zoom into the image.

The mission: stamp out fuzzy photos

I don't care if you're posting

for a syndicated reality TV show, an A&E documentary, or

even a cloying AMC "Back Story" leveraging yet another

shelf of the immense 20th Century Fox archives of dead star stills

into formulaic all-new programming-- there is no excuse

for fuzzy photos. Soft, pixellating digital photo animation is

everywhere these days. It telegraphs cheapness and disregard

for craft. The goal here is to scan your photos to keep pixels

out of the picture, and leave you with the resolution limits

of the photo grain itself-- unless of course that's the effect

you really want, along with lower Neilsons.

Does this mean you should immediately

scan all your photos at 1200 dpi? Heavens, no, not unless the

photo is 2" wide and you want to zoom into it 5 times normal

for NTSC D1/DV. (You'll see shortly why I was able to rattle

that off so quickly.) Over-rich scan rates are way overkill and

for larger images put real strain on your processing power, which

invites odd display behavior, file corruption and outright freezes,

lockups and crashes due to import limits. There are always

limits, you see. The trick is how to leverage them for your

creative needs.

In August 2001 LAFCPUG's Ken Stone, also a professional photographer,

provided a nice tutorial

on scanning photos for video, showing how to factor a zoom using

two very cool freeware tools. Don't lose those! Tom Wolsky, another LAFCPUG headliner, also

provides a cogent treatment of scanning in the newest version

of his awesome Final Cut Pro 3 Editing Workshop,

from CMP Books, (and yes, my FCP KeyGuide™ is proudly included).

This tutorial takes all that wisdom a

step further and simplifies the process of getting exactly what

you need in pixels into Final Cut Pro and only what

you need-- to work creatively within import limits, to fill the

frame, to zoom in, to reduce render times and strain on the CPU

which comes from tugging around a huge imported graphic while

trying to animate it and above all, to keep the image as crystal

clear as possible.

To make this exciting and dynamic, prepare

a scanner, photos, Photoshop and FCP to play with.

To assist me I'm using the new ScanGuide™ Pro, a two-sided laminated

reference I developed for just this need. I'm frankly excited

about its utility and I hope it's contagious, because a fair

amount of research and design went into it. (The ScanGuide Pro

is available in the LAFCPUG

store.)

|

ScanGuide™

Pro helps you plan photo zooms that stay sharp, no matter what

format. |

Observe Posted Limits

ScanGuide™ Pro sports built-in safety ranges which observe

graphic import limits. In a typical ScanGuide™ Pro column

header you'll note zoom multiples listed in white,

and then yellow. The white listings keep your scans under 4000

pixels-- Final Cut Pro's current import limit. The yellow listings

keep you within 16,000 pixels, easily accommodated by After Effects®.

Listed below each multiple is the scanrate needed to achieve

it, for image widths from 1" to 14" wide.

White

multiples safe for FCP; yellow for After Effects.

So what's all this fuss about pixel limits

anyway? The 4000-pixel limit is built into current QuickTime

architecture. This will definitely change; it becomes an issue

as more of us get into High Definition post and need deeper scans

to cover bigger image areas. Thus far two major HD formats have

concretized: the Sony 1080i/p standard, with a 16 X 9 window

measuring 1920 X 1080 pixels, and the Panasonic 720p format,

with a 16 X 9 window measuring 1280 X 720 pixels. ScanGuide™

Pro provides scanning tables for both. (For those of you designing

for direct film recording, there's a 16 X 9 Cineon table too.)

A glance at these tells you immediately you're in "yellow

alert": HD photomotion is currently an After Effects game.

After Effects® sidesteps the QuickTime

import limit by implementing its own rendering engine, hosting

up to 30,000 pixels square. At 16,000 pixels maximum the Pro

guide keeps you well within current limits anywhere on the sheet.

Best Scanning Content Candidates

- Continuous-tone black and white

or color photo prints. Photos from magazines or newspapers are

usually printed using the halftone dot screen system, and your

scanner will collect them exactly that way. Unless you apply

a descreening filter at the source or treat it in Photoshop,

the result can be a distressingly bizarre vibrating display called

a moiré pattern.

- Digital camera stills of 2.5 megapixels

or higher, which give you more than the data you need to zoom

in. Suddenly iPhoto becomes relevant to your workflow because

photo image capture is effortless. Rehearse zooms, see if you

have enough pixels for magnification.

Cop it, Crop it

Let's start with your raw flat

art: photos! Knowing that storytellers must proceed based upon

what they can get for scanning-- be it an aging treasure map,

a ripe 3" square Polaroid snap from a family scrapbook,

or an 8" X 10" glossy of his legendary brother Phil

at the Michael

Ochs Archive -- ScanGuide™ Pro lists them as a range

of image areas from 1" to 14" wide, with accurate ratio

heights depending upon the selected video format.

As Ken indicates in his tutorial, you

often want to crop the original and scan only a portion of it.

Most scanner software allows you to do just that in situ.

Just because your photo is 8" X 10" doesn't mean you

need to scan the whole photo. Pre-edit and keep that pixel count

down!

Plan, Then Scan

Once you've determined the actual

desired width, you can determine the height needed from the Pro

guide. Not everything you encounter will be conveniently 4:3

or 16:9-- that's life, but it's still annoying. For instance,

suppose we're dealing with an odd-sized wallet photo. Here's

my cute niece Alexa, original size, 2 1/2" X 3 1/2".

(She's since grown considerably.) I refer to the Pro guide to

quickly derive the required frame height for 4:3 and for 16:9

aspect ratio at a 3" width.

Now this may interest you: I choose the

3" width line because I know from experience there's conservatively

15% "wiggle room" for zooming. That is, up to a point

you can let FCP's QuickTime (or After Effect's) display engine

do some inventive, barely detectable pixel pushing for you--

it helps keep the file size down, too. Small photos generally

need very rich scans.

First I'm concerned about composition.

Pro guide tells me I'll be cropping the SD 4:3 vertical to 2

1/4". That's fine, I can always animate a tilt-up to her

face. I also know cropping becomes more severe for SD 16:9--

1 11/16" height!-- and it puts her into a choker, but I

want that too because widescreen is so cool! I can intelligently

plan "baseline" scanrates to fill either video frame

and start worrying about magnification.

Zooms Loom, Avoid Doom

The results of scanning only

for 100% width and risking a 4X zoom-in, rather than judiciously

scanning for it, are illustrated below. Want to get out of cable

access TV and into PBS or not?

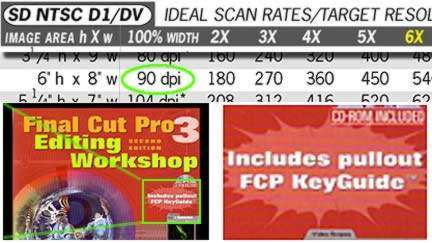

| 90 dpi "Baseline"

scan of this 7 1/2" wide cover looks great at 100%... |

... but falls apart

when zoomed in 4X. |

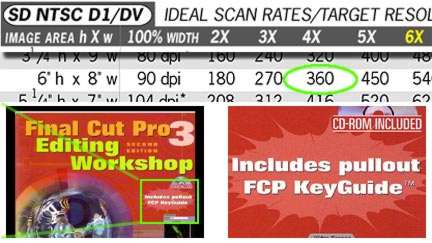

| 360 dpi "4X"

scan looks good at 100%... |

...and just as clean at 4X

zoom, after treatment for moire. |

You can determine zoom factor as a rough

calculation. For instance, assume you have an 8" H X 10"

W, you intend to start wide, and zoom into an area of interest

measuring about 2 inches across. What's the zoom factor, class?

5X! Now look it up on the 10" width line, under "5X"

to get the ideal scanrate to support the zoom-in. For this width,

zooming in five times, NTSC DV 4:3, it's 360 dpi. Make it so!

Which reminds me of another Ken Stone

wisdom-- it's fine to overscan slightly for flexibility. When

you come up with a fractional factor, it doesn't hurt to go for

the next higher zoom multiple. Many scanrates supplied in the

Pro guide are in fact slight overscan rates which hit even numbered

dimensions to avoid video weirdness.

So what do we know or infer thus far?

- That physical photos need to be scanned

to be imported into FCP.

- That a high-resolution scanner is a

good idea, and they're now cheap.

- That there are zillions of fine photos

in the 20th Century Fox archives.

- That to scan small photos to render

properly at 100% width, scan rich.

- That to maintain sharpness at the close

end of a zoom, scan richer.

- That a scan for SD won't work well for

HD; scan even richer.

- That you can scan direct, or overscan

for touchup, and then downsample.

- That there are absolute dimensional

limits to graphic import sizes-- depending.

- That ScanGuide™ Pro will guide

you through scanning based upon your photo image area, your zoom

requirements, your video format and your import limits, for $19.95.

Workflow Tips and Techniques

I don't care how miserly you are with

your pixels: never scan in Line art mode--

that's way too little data. You want at least 24-bit grays or

colors to work with, in RGB format. That mode assigns each pixel

one of 16.7 million available colors.

Overscanning is a very common strategy,

but this can result in huge file sizes-- a 6" X 8"

image scanned at 1260 dpi for DV can support a 14-to-1 zoom-in--

anything but film grain down there? But as a 24-bit file it can

weigh in around 220 megabytes! Do you really need all that data?

Storage isn't the problem these days; it's the processing, applying

filters and ultimately the time rendering your animation of that

image that gets expensive. Especially if you're doing one of

those fabulous Ken Burns-type photo documentaries about another

cool dead white guy and you've got 30 dozen of these photos to

process. (Which is why Ken's producers only scan low rez for

rehearsal animation in the NLE, and use Frame Shop to shoot final versions with motion

control on film, to be repurposed anyway they like-- an

efficient and sensible workflow.) Of course most of us working

in DV/DVCAM/Beta with fewer pieces to animate can scan for output

resolution from the start.

But why would you overscan rather than

scan direct at an ideal scan rate? Well, as Ken Stone points

out, the downsampling algorithms in Photoshop are sophisticated

and help preserve the highest tonal quality and detail. It's

especially useful to overscan if your scanner is not calibrated

via Colorsync profile to your monitor, or the photo is of secondary

quality, or major touchup is required. We like to deal with such

issues at a deep scanrate in Photoshop. For this scenario, downsampling

to an ideal target resolution which still allows you to zoom

in and stay sharp-- is a good thing. It's good bit budgeting.

You decide.

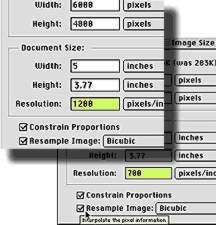

To downsample -- always the final

operation (before pixel resizing and saving) -- you merely open

Photoshop's Image Size window, keep the image dimensions just

as they are but change the Resolution value to the recommended

DPI listed in ScanGuide™ Pro for the X factor you desire,

and make certain the Resample checkbox is checked. That's it.

|

At

6000 pixels wide this photo cannot be safely imported into FCP

or even Avid systems! Downsampling-- a form of resampling-- reduces

file size and cleverly removes excess pixels. |

While downsampling, keep an eye on the

Pro guide's Zoom Multiple heading. If you discover you must downsample

to a value "in the yellow" for desired zooming, you'll

be importing the scan into After Effects® and animating there,

so prepare to wrestle keyframes to the ground. For instance:

you scan a 5" snapshot for DV 16:9 widescreen dimensions.

You've also decided you'll need to zoom in 4X for dramatic punch.

On the Pro guide, the 5" width line reveals the 4X zoom

multiple to be listed in white- hey, cancel Yellow Alert! You're

still okay for FCP.

Image Adjustment Before Final Import

If you're stuck scanning halftone sources,

try to find the highest quality available and be prepared to

introduce 1 pixel of Gaussian Blur in Photoshop, to fuzz the

edges of halftone dots to help avoid the bizarre collision of

dots and video scanlines-- major moire. Believe it or not, small

blur -- 1 pixel or less-- can actually enhance some details on

video.

The most common scanning hazard deals

with very fine lines of detail measuring 1 pixel thickness or

less. Rich scans carry a lot of fine detail! These invite scanline

twitter especially along horizontals, because the import

just doesn't know where to place the detail --on one scanline

or the one below. During a zooms, this can be a horrible thing.

Sometimes performing a subpixel reposition of the clip itself

solves this, but the best strategy is to apply a 1-pixel Gaussian

Blur to the scene.

A phenomenon you might notice after a

rich scan is what're all these twinkly white dust spots? Even

after assiduous cleaning of the glass bed and the artwork, twinkly

white dust spots pop up. Eliminate these through image editor

touch-up tools before importing to FCP. Otherwise during zooms

they'll twinkle like stars on a cheap B-movie backdrop-- a "mini-moire"

effect.

Almost every uncalibrated scanner requires

some compensation for introducing too much green, red or blue

from the scanning lamp itself. Best done in Photoshop with Color

Balance tools.

If your scanner software allows you to

set a white and black point, this is an opportunity to build

a proper tonal scale right into the scan, (that's a Ken Stone

tutorial too) but again, many would rather do it afterwards in

Photoshop, especially since the scanning software is usually

a Photoshop plugin which brings the image right into the program.

There you can also apply the NTSC Safe Color filter and set your

Output Levels.

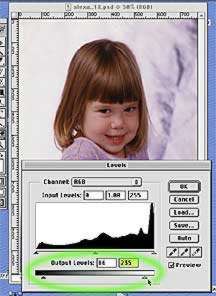

|

Output

levels for legal video: typical image adjustment in Photoshop

|

It's common to adjust the digital Levels

scale in Photoshop to the NTSC setup and white point level standards.

To properly render video levels of a computer scan, boost the

Levels Histogram black value output from 0 to 16 and the white

level down from 255 to 235. Lo and behold, without getting technical,

if you import this file and examine its readout in the FCP Toolbench

Waveform scope, the setup and white values will be legal. If

for some reason they are not, stay right inside FCP and apply

the Broadcast Safe filter, it's been blessed by professionals.

Video Monitor Previews

As with all image editing in

Photoshop, it's extremely valuable to preview your work on a

broadcast monitor, to evaluate color, applied blurs and other

enhancements affecting the image on video. If you employ one

of the qualified analog capture cards , use its live video preview,

or just get the software-based utility Echo-Fire™, a magnificent tool which

pumps the Photoshop or After Effects image out the FireWire port,

through your camera or deck to your client monitor. It also gives

you video scope overlays to check legal video values. Either

strategy eliminates many nasty surprises.

|

EchoFire™

provides a convenient, accurate software-based graphic preview |

The Resizing Rumba

Most video editors working in

Standard Definition NTSC or PAL know the resizing dance to correct

graphics for square to rectangular TV pixels, to prevent a perfect

circle from looking like an egg in video. The nice thing about

the HD formats is that we don't need to futz about compensating

for differing pixel ratios anymore. In HD, all is square, from

your Photoshop scan to final delivery format. All is square throughout

the upcoming workflow. I cannot get over it. Meanwhile, ScanGuide™

Pro provides the scaling factors required for both current NTSC/PAL.

Image Adjustment After Final Import

We've waded through all these

issues so you can finally import the photo, and start swimming.

Your import, for one reason or another,

might not display exactly as you expect right off the bat. A

rich scan may overfill the Canvas when you first view it. Don't

panic. Double-click the clip in the timeline, select the Motion

tab of the Viewer. The culprit is the Scale value, and it's easily

reset here. Experiment with values. See what the import looks

like at 100%. See if you get your wide shot by scaling back--for

instance, if you scanned for 5X, back the Scale off to 20%.

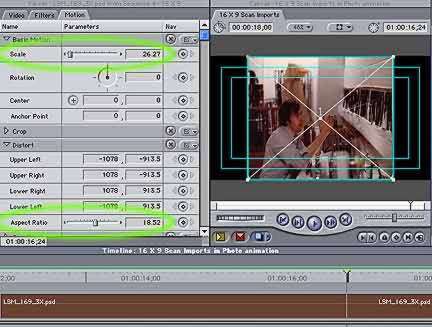

|

A

3 1/2" X 5" snapshot scanned for SD 16:9 format and

3X zoom factor!

The scanrate to achieve this: 525 dots per inch. |

You will likely encounter oddball scaling

situations, such as the above scan for a Standard Definition

anamorphic widescreen sequence, which is fun to work in. The

original snap was a 3 1/2" X 5" snapshot of some poor

devil negative cutting A, B, C and D rolls back in the late 70's.

(The shot was taken by Michael Korolenko, and his film Since

'45 became a Student Oscar winner.) It was scanned rich for

a 3X zoom. Let's see what happens on import.

|

The scan

comes in squished horizontally and scaled to the vertical. Notice

odd Scale and Aspect Ratios. Ready to give up and return to real

estate? Wait!

|

|

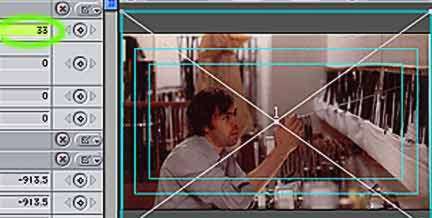

First

we expand the image to the original proportions by zeroing out

the Aspect Ratio. |

|

Now we can begin to play with our pre-built scan

values. Since the scan was 3X, change the scale from the oddball

import value to 33%. This fills the frame with a wide shot. Top

and bottom are cropped-- you're not surprised by that-- and it

gives you compositional room. |

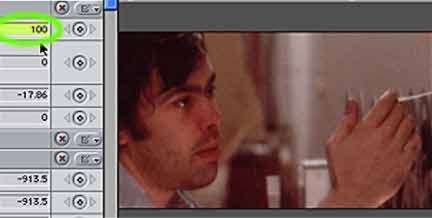

|

Finally,

check the planned zoom by setting Scale to 100%. Hey, isn't that

the young Tim Curry...? |

Photomotion itself is another topic altogether

and best learned in a good class, from an able practitioner,

or competently written procedural text along with your own time

noodling the tools. But it all begins with acceptable source

materials and your ability to scan smart puts you ahead.

Conclusion

Scan rates are really nothing

you couldn't figure with a calculator...but there are many variables:

photo image area, zoom intent, aspect ratios, resizing, alien

workflows, el niño, the stock market. To save you

time, it's all been integrated for you, all the popular international

video systems, for deep zooms, for any practical width from a

1" postage stamp to oversize 11" X 14 " prints,

in ScanGuide™ Pro.

Scan away, stay sharp, and don't make

me come down there with the big shoes: stamp out the fuzzies!

Grateful Thanks to

Ken Stone, Phil Hodgetts, Trish and Chris Meyers, Michael Korolenko,

Tom Wolsky

and of course, Alexa.

Click HERE to download the PDF

Version of this article. (4MBs)

You must

have Adobe Acrobat  to view the PDF version.

to view the PDF version.

When

he's not obsessing over fuzzy photos, or differences between

Avid and FCP splicing buttons, or annoyances of the OSX interface,

Loren S. Miller is an award-winning documentary producer,

freelance editor, screenwriter, project consultant, graphic designer,

editing teacher, reporter, author, active member of both Los

Angeles and Boston Final Cut Pro User Groups, developer of ScanGuide™ Pro, and KeyGuides™ for major Macintosh media

authoring software. Reach him anytime at neotron@mindspring.com.