|

|

|

Techniques: Photoshop Titles

|

July, 2002

"Photoshop Titles"

By Tom

Wolsky

About this article:

The

article is adapted from the book Final

Cut Pro 3 Editing Workshop

by Tom Wolsky.

To purchase this book or for more information, click HERE.

Because the titler was so weak in earlier

versions of Final Cut, many people, myself included, took to

using Photoshop as the FCP titler. What a great titler it is,

infinitely malleable, with many additional elements, like banners

and bars and gradients, which are more difficult to construct

in FCP than in this great graphics application. Anything you

can imagine is possible. I use it often, particularly for lower

thirds, but also for working with still images that need to be

incorporated into a project.

What you should first know about working

in PS is that you should only use RGB color space - no CMYK,

no grayscale, no indexed color. They don't translate to video.

One problem with using PS is the issue

of square versus nonsquare pixels. Because PS is a computer program,

it works in square pixels exclusively, while most video uses

the CCIR601 or rectangular pixel. This presents a minor problem.

The important point is to understand how FCP handles still image

files. It handles different sized images in different ways. Single

layer files are treated one way, multilayer Photoshop files or

PS files with transparency are treated another way.

1. If you're working in the DV format

using CCIR601 pixels at 720x480, create your PS files at 720x534.

If you're working in standard CCIR601 format, 720x486, then create

your PS files at 720x540.

Preset Sizes: If you're working with Photoshop 7, there's a

neat new feature that allows you to select preset custom sizes

when you make a new file. Use the Preset Sizes popup and select

either 720x540 Std. NTSC 601 or 720x534 Std. NTSC DV/DVD.

2. After you've made your graphic, go

to Image Size and, making sure Constrain Proportions

is deselected and Bicubic is selected, change the

height of the image to 480 or 486, as appropriate.

This squashes the image down, distorting

it, changing it to a file that FCP recognizes as using CCIR601

rectangular pixels.

3. Save your file. I save out a separate

PS file that has been converted to CCIR601 format and keep the

original so I can correct the typos I usually make.

When you bring a PS file that's 720x480

into FCP, the editing software assumes it's been prepared for

use in a DV sequence.

When placed in a DV sequence, the image

will work perfectly and be treated as a nonsquare pixel image.

You're not always making a graphic that

needs to fit in the video format. Sometimes you're making a graphic

that is much larger, one you want to move around on to make it

seem as if you're panning across the image or zooming in or out

of the image. To do this, you need to make the image much greater

than your video format, perhaps 2,160x1,602 pixels or more.

If you are working with a Photoshop layer

image, you still should squeeze the image down to nonsquare pixels

before you bring it into FCP. To do this, rather than using pixel

values, use percentages and reduce the height of the image to

90% or, if you want to be anally precise about it, 89.886%. Again,

you should not resize these images if they are single layer images

without Photoshop transparency. FCP understands these are square

pixel images brought into a CCIR601 world and will handle them

appropriately.

If they are PS layered files with transparency,

FCP treats these as separate sequences and does not adjust for

CCIR601 pixels. The rules of the road are probably unnecessarily

complex, but the bottom line is if it's a single-layer file,

let FCP do the resizing; if it's a PS file, squeeze it before

you import it.

The easiest way to work with Photoshop

files that you want to lay over video is to create your PS files

over transparency, PS's checkerboard background. This transparency

will be honored when you import the file into FCP. It's important

to understand that PS files come into Final Cut as separate sequences.

This means that when you bring a PS file with multiple layers,

all its layers remain intact as separate layers in a FCP sequence.

There each layer can be animated and affected separately.

The only time Photoshop files do not import as a sequence is

when they are made up of a single background layer or are saved

as flattened images or in some other file format, such as PICT

or TIFF. Note: there appears to be a problem importing large

format TIFF files into FCP3 under OS X.

Because it's simpler to work with a single-layer

file, I often convert my PS files to PICT images, preserving

the transparency information in an alpha channel, a simple procedure

and easy enough to create a PS Action for. I retain the PS file

to make changes after the following procedure.

1. Collapse the PS layers so that they

merge over transparency.

2. Command-click the layer to

select the contents of the layer.

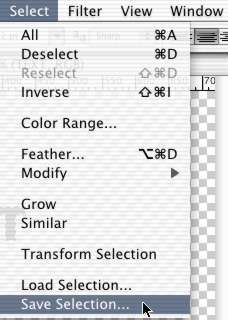

3. Go to the menu bar to Select>Save

Selection (Figure 2) to bring up the Save Selection dialog

box.

Figure2

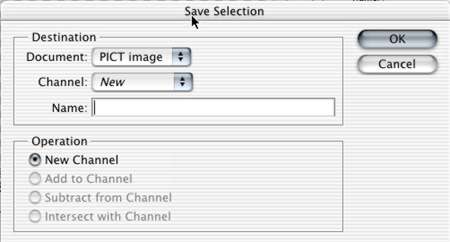

4. Save it as a new channel, as shown

in Figure 3.

Figure3

If you look in your Channels tab,

usually behind the Layers window, you'll see that you

now have four channels, the three color channels - Red,

Green, and Blue - and a channel called an Alpha

channel (Figure 4).

Figure4

This is a grayscale representation of

opacity. Whatever is white in the alpha channel will be opaque

on the screen; whatever is black in the alpha channel will be

transparent. Various shades of gray in between will define greater

or lesser amounts of opacity.

Because video is interlaced and often

produces flicker in text, I like to apply a slight amount of

blur to mitigate this.

You have to select the whole layer -

not just the content - or the blur won't have any effect.

1. Use Command-A to select the

entire layer.

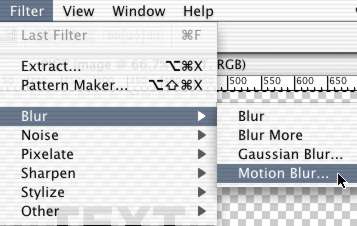

2. Then from the Filters menu

select Motion Blur (Figure 5).

Figure5

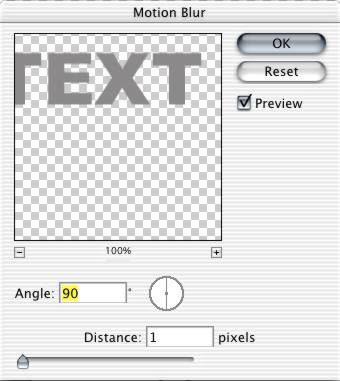

This opens up the Motion Blur dialog

box (Figure 6).

Figure6

3. Set the blur to vertical and the amount

to one pixel.

This produces an ever-so-slight vertical smearing, just enough

usually to offset the jittering created by interlaced fields.

4. Put a black layer behind the content

layer.

I do this because PS collapses an image to a white background,

producing white fringing around the alpha edges of the content.

It premultiplies the image with white, mixing the antialiasing

on the edges of the text with white. This doesn't look very good

over video. Adding the black layer will force PS to premultiply

and mix the antialiasing with black, which looks better on video.

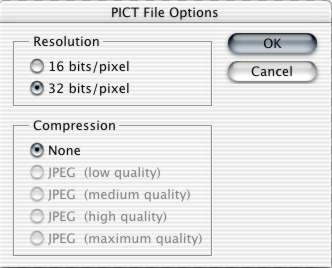

5. Saving the file brings up the dialog

box in Figure 7.

Figure7

6. From the Format popup, select

PICT File. Make sure the Alpha Channel checkbox

is checked.

7. Click the Save button to call

up one more dialog box (Figure 8).

8. Set the Resolution to 32-bit.

It's eight bits per color channel, plus another eight bits for

the alpha channel. Do not compress the image. Compression will

lose the alpha channel.

That's it - you've made your PS file

into a single layer PICT file with transparency.

When you import an oversized Photoshop

file and place it inside a sequence, FCP will immediately scale

the image. If the still is smaller than the image resolution,

say a 500x200 image in a 720x480 DV sequence, the application

will simply place it in the center of the screen with blackness

around it. If the image is, say, 400 pixels wide but 800 pixels

tall, FCP will scale it down to fit inside the window, as in

Figure 8. If you do want to use the image at its full size, so

that you can move across it, for instance, the first step you'll

have to do is to return it to its full size.

1. Select the image in the Timeline

and hit the Enter or Return key. Or Option-double

click on it to open it into the Viewer.

2. Click on the Motion tab in

the Viewer.

3. Set the Scale value back to

100.

Be careful that any Photoshop file you

import into FCP3 has no empty layers, or adjustment layers, or

layers with effects applied that have not been rasterized. Trying

to import a file like this can cause an Out of Memory error message

when you try to bring the file into FCP3 under OS X.

For people who come from a print background,

the important point to note is that video doesn't have a changeable

resolution. It's not like print where you can jam more and more

pixels into an inch of space and make your print cleaner, clearer,

and crisper.

Pixels in video occupy a fixed space

and have a fixed size, the equivalent of 72dpi in the print world,

which happens to be the Macintosh screen resolution. Dots per

inch are a printing concern. Forget about resolution. Think in

terms of size: the more pixels, the bigger the picture. Do not

think that you can make an image 720x480 at a high resolution

like 300dpi or 600dpi and be able to move it around in FCP. Certainly

you'll be able to scale it up, but it will look soft, and if

you scale it far enough - to 300%, for instance - the image will

start to show pixelization. FCP is good at hiding the defects

by blurring and softening, but the results are not really as

good as they should be. FCP is a video application and only deals

with pixel numbers, not with dpi.

Scanners, on the other hand, are designed

for the print world where dpi is an issue. Because scanners generate

lots and lots of pixels, this is very handy for the person working

in video. This means that you can scan an image at, let's say,

300 or 600dpi, even a quite small image, and your scanner will

produce thousands and thousands of pixels, which will translate

into video as a very large image. You now have an image that's

very much larger than your video format of 720x486 pixels. If

your scanner can generate an image that's 2,880 pixels across,

it's making an image four times greater than your CCIR601 video

frame. You can now move that very large image around on the screen,

and make it seem as if a camera is panning across the image.

Or you can scale back the image, and it will look as if the camera

is zooming back from a point in the image. Or reverse the process

and make it look as if the camera is zooming into the image.

copyright©2002Tom

Wolsky

The

article is adapted from the book Final

Cut Pro 3 Editing Workshop by Tom Wolsky published by CMP books. To purchase this book or for more information,

click HERE.

About Tom

Wolsky

Tom is the author

of Final

Cut Pro 3 Editing Workshop, He graduated with honors from the London School of Film Technique, spent several years as a screenwriter; then worked at ABC News' London Bureau and in New York as a producer and operations manager for nearly 20 years at World News Tonight, World News Now, and Good Morning America. He's been teaching Television and Video in Northern California since 1992 and added Final Cut Pro to his editing repertoire 2 years ago.

He has his own production company, South Coast Productions, which

is based on the Media100, and is currently working on a short

documentary for the Mendocino Land Trust.

About the book

FINAL CUT PRO

3 EDITING WORKSHOP complements Apple's documentation with a series

of tutorials that teach readers the art and technique of editing

with Final Cut Pro by working through 13 lessons. Tutorials cover

the complete range of tasks, from installing the application

to outputting. All of the necessary materials, including raw

video footage and sequences, detailed instructions, tips, and

principles taught in film schools, guide the reader to a working

knowledge of Final Cut Pro. The companion CDROM contains everything

needed to perform the exercises, including raw video footage

and sequences

|