|

| Tutorial: Line your own Nest: Basics of Nesting in Final Cut Pro |

August, 2002

Line

your own Nest: Basics of Nesting in Final Cut Pro

By Charles

Roberts

Although nesting is arguably one of the

most useful and necessary components of any compositing application,

its always shocking to find how many people really don't understand

it in a fundamental way. This is largely because nesting isn't

an effect or plugin in a filter menu. It is rather a procedural

element, a part of your workflow that makes things possible which

could not be accomplished otherwise. FCP, After Effects (where

it is called Pre-Comping), Commotion (where it is called Grouping),

and many other applications leverage the ability to build another

dimension of control into composited effects workflow.

What is it?

First, what is nesting? At least

as far as FCP is concerned, nesting is simply a sequence that

acts as a clip inside another sequence. How do you nest a sequence?

There are two ways to do this that only differ in the manner

of execution. The resulting nested sequence is precisely the

same in functionality. The first way is to select a number of

clips in a sequence and go Sequence>Nest Item(s). On this

command, FCP will ask you to name the new nested sequence, choose

a sequence preset for it (since the nest will be a true sequence)

and allow you to mixdown any audio tracks that might cause the

nested sequence to exceed the number your Mac is capable of doing

normally (you should generally do this anyway).

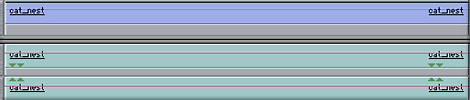

After doing this, the selected clips

will form a single clip (the nested sequence) on the Timeline

displaying the name you just used in the dialog box. An icon

for this new sequence will also have appeared in the Project

tab of the Browser window bearing this name. Want to get access

back to the clips you just nested inside this sequence? Simply

double click the nested sequence-in-a-sequence, or double click

the nest sequence in the Browser to open it in the Canvas/Timeline.

Since a nest is simply a sequence, you can always load it to

get to its contents.You can also Option-double click a sequence

to load it into the Viewer window, if you want to apply effects

to it like a clip.

The second way to create a nested sequence

is almost too easy. Simply drag one sequence from the Browser

(or Viewer if you have loaded it there) into another one in the

Timeline. There you have it; a sequence is nested in another

sequence. It is now being treated as if it were simply an individual

clip. In fact, you can do anything you would do to a clip to

the sequence, such as loading it in the Viewer and applying Motion

and Filter effects. But we get a little ahead of ourselves...

Why bother?

Once you have the concept down, its pretty

easy to put Nesting to work for you. There are two main reasons

for using nesting techniques: render order and render file protection.

Render order is of incredible importance to anyone engaged in

any sort of effects work. Remember that not all effects work

is light sabers and morphing! Something as simple as applying

a widescreen matte to a 4:3 picture or picture-in-picture effects

can be accomplished much more quickly and efficiently if one

uses the power of nesting rather than applying such effects to

clips individually.

If you have a range of clips to which

you need to apply the same effect, Nesting allows you to apply

any effect to the entire range of clips at one stroke. In addition

to speeding up your workflow from only having to apply a filter

once (and potentially remove it once if it doesn't do what you

want!), you also get the benefit of only having to change the

values of one filter to affect all the clips in the nest the

same way.

To make a bad analogy, say for instance

you are watering plants. If they are scattered all over the house,

it might take you all afternoon to apply the same amount of water

to them all. However, if you move them all into the same location,

i.e. nest them, you could probably hose them all down in less

than a minute. Same goes for clips and sequences.

And let's not forget that it isn't just

about applying effects filters. While nesting might speed up

the process of applying one filter to many clips, it is an absolutely

necessary procedure for some types of picture-in-picture and

other motion effects. Say for instance you want a sequence of

video clips you have scaled down to thumbnail size to move across

the video frame. If you tried to line up all the clips and enter

all their individual motion settings to perform this simple visual

stunt, you would quickly find that it is impossible to figure

out such values. The motion would be flawed, jerky and uneven,

if you even managed to get close to the correct values. All you

had to do was line up the clips as you want them to play in a

sequence and nest it. Then apply the motion you want to the entire

nest. This is an example of something that really cannot be done

without nesting.

When to use it

But should you always apply your effects

to a nest? To effectively use nesting as a tool, you have to

have a correct understanding of render order. Some items can

and should be nested, while others should not. What determines

this? Ultimately, you work this out by evaluating how individual

and specific the effects settings will be for each clip that

you are considering nesting.

A good example of this consideration

would be the case of applying a widescreen matte to a 4:3 picture

and performing an Offset, or pan and scan, to move the area of

the 4:3 frame into the widescreen matte viewing area. Because

widescreen's aspect ratio is different from the 4:3 video rectangle

we are used to (shorter and wider), a 4:3 picture that is cropped

to imitate widescreen offers the editor the ability to move the

4:3 picture around behind the matte and focus on different parts

of the 4:3 frame. We don't see that the 4:3 picture has been

shifted around because the widescreen matte is blocking out its

true edges. It gives the editor one more chance to tighten up

a shot that the DP either couldn't or wouldn't compose tighter

in the frame.

The amount of up or down positioning

of the 4:3 picture behind the widescreen matte is called its

Offset. Since we have this freedom to focus on the specific areas

of the 4:3 frame, we will likely want to adjust the offset of

EVERY clip individually that we are widescreen matting, until

we have it all framed perfectly. If we apply the Widescreen filter

(Effects>Video Filters>Matte>Widescreen) to a clip and

look at its Filter control tab, we see that in addition to being

able to set the size of the crop by its aspect ratio, we also

have a control to manually set an offset for the clip to get

it lined up the way we want.

Unfortunately, applying the Widescreen

matte filter to each clip, then applying individual offset settings

to each clip would be painful and slow. The key here is render

order; knowing what is more efficiently accomplished through

nesting and what is not. In this case, we would be more efficient

if we edit all the clips in order, then nest them, and finally

apply the Widescreen matte filter to the nested sequence.

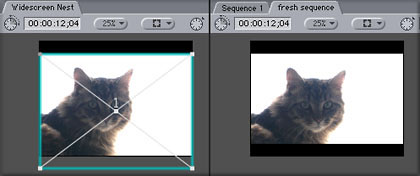

Of course we still haven't given the

clips the individual offsets they require. Double click the nested

sequence and go back into the original nest contents. Then simply

reposition the individual clips using the good old Canvas and

Viewer wireframe tools and Motion tab settings. If you have both

Canvas tabs visible for each sequence, you will see the effects

of the motion settings of the nested sequence's contents ripple

forward and be displayed in the parent sequence tab.

To make this clear, here are the steps

in brief order:

1)

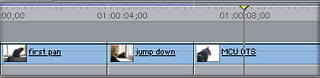

Start with a fresh sequence. Edit the clips in the order you

want them to appear.

2)

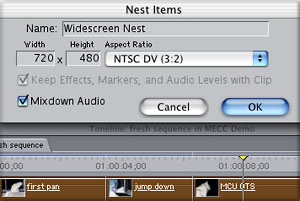

Select all the clips, then choose Sequence>Nest Item(s). Name

the nest "Widescreen Nest" and enable Mixdown Audio

3)

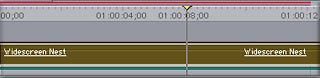

Select the "Widescreen Nest" sequence in the Timeline

and apply the Widescreen Filter (Effects>Video Filters>Matte>Widescreen)

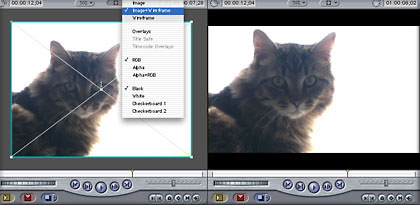

4)

Double click the "Widescreen Nest" sequence in the

Timeline so that it loads into the Canvas. While it is loaded

there, tear away the tab and place it side by side with the Canvas

tab for the original, or parent, sequence so that you can observe

how the changes you make in the one window are reflected in the

next.

5)

Make sure that "Widescreen Nest" Canvas tab is set

for "Image and Wireframe", then make rough position

adjustments directly in the Canvas tab for "Widescreen Nest"

You should see the position adjustment

ripple up into the parent Canvas tab. Just make sure that you

are moving your playhead up with each clip you adjust. The best

part of this process is that if you are using an RT capable Mac

G4, the Motion tab settings for clips are RT-enabled. You won't

be able to play back the parent sequence that has the Widescreen

filter applied without rendering, but you can play back the "Widescreen

Nest" child, the offset of which is being corrected through

simple Motion tab changes that are RT-savvy.

The upshot is that we have used nesting

where it would save us an enormous amount of tedious work and

rendering, but not used it where it would have been irrelevant

or counter-productive.

The other benefit

There is another, less obvious benefit

to using nesting in FCP: Render File Protection. In FCP's media

management system, render files are maintained through their

links to a sequence. Each frame of rendered video is linked to

a specific frame in a specific sequence. This is why when you

copy a rendered clip and paste it into another sequence or project,

you have to render it again; it lost its link to the sequence,

and thus its render files.

All of us at some point or other while

working in FCP have accidentally committed an action that un-rendered

our video. Sometimes this is as simple an action as adding a

keyframe or edit point to a clip that has previously been rendered.

Even picking up a rendered clip and moving it on the Timeline

can lose the render files. When that red line jumps up on the

Timeline, our fingers go racing for the command-Z Undo!

But there is a way to make the render

file management system work for us rather than against us. When

you nest a group of rendered clips, you isolate these original

clips and their links to their render files from any form of

editing by linking their render files to the new nested sequence.

As long as you don't go messing around inside the child sequence,

the render links will remain intact. This makes it possible for

you to perform edits on the rendered material without un-rendering

it since you are really only editing the parent sequence and

not the rendered clips themselves! You can trim, keyframe and

cut away to your hearts desire, even move the nested sequence

around in the Timeline without ever jeopardizing the integrity

of the original rendered clips. Although it may seem like no

big deal, this saves tons of time-wasting renders when you experiment

a lot with clip order.

There's gotta be a catch!

That sounds just great, Chawla! Isn't

there anything negative about this powerful nesting procedure?

Well, as usual, great functionality comes at a cost. Nesting

does eat up system resources, so you have to be a little strategic

in nesting.

One of the most common issues with nesting

is that it bloats RAM usage and project file size. Every sequence

in use by a project loads into RAM. Each frame of a sequence

is actually a link back to a frame of video media on your hard

drive. As such, when a sequence is loaded into the Timeline and

Canvas, it takes up a big chunk or the available RAM, regardless

of whether you are playing the sequence back or not. Having thirty

sequences loaded up at a time can jack your RAM usage through

the roof.

In OSX, RAM allocation is performed behind

the scenes by the OS, which can result in Virtual Memory pageouts

kicking in and declining performance if you don't have enough

physical RAM to go around. In OS9, where you still have to assign

a RAM allocation to each application, having too many sequences

loaded can actually cause crashing, Type 1 and 2 errors or even

possibly project corruption. Although the conventional wisdom

is that FCP wants no more than about 200 MBs of RAM allocated,

you have to go much higher than this if you are using many sequences

simultaneously.

And the more complicated your nesting

gets, the more sequences that will have to be loaded simultaneously.

There is no real practical limit to the depth of the nesting

you can create. You can nest sequences inside sequences inside

sequences until its turtles all the way down, as the saying goes.

The problem is that all those sequences have to load into RAM,

and if you have RAM limitations, you can run into trouble.

Another problem that is common is the

speed issue. It can take a long time to load up the correct rendering

of a frame if its appearance depends on tracing its steps through

four or five nests. You will likely find that keyboard navigation

commands and device controllers like jog/shuttles and such get

a little (or a lot!) sluggish when you start getting deep into

the nests. If you don't like getting the "Preparing Video

for Display" message, well, your life isn't going to get

any simpler after you've nested eight layers deep!

Finally, the size of your project grows

with each added sequence. Each sequence you add through nesting

adds to this in project density and complexity. And if your sequences

are long as well as deeply nested, your project size can swell

all out of proportion. Sometimes the difference between a 10

MB project file and a 60 MB project file is a couple of two hour

long nested sequences. And although I don't have any hard physical

evidence, I have seen projects tank and exhibit strange errors

once they get super-bloated. Eliminating a few extra, unused

sequences usually clears up the problem.

So, you can see that some strategy has

to go into nesting. Its a powerful tool in the hands of a person

with vision and a deadline. But you have to use it where it will

help you and make sure you aren't letting it restrain you in

the process. As usual, the only way to really understand it is

to use it a few times. Practice, as always is the best teacher

there is. Have fun!

Charles Roberts teaches Video and Digital Media in the

Communications Media Department at Fitchburg State College in

Fitchburg, MA, and is the author of "Final

Cut Pro 2 for Firewire DV Editing", published by Focal

Press. He spends what little free time he has coming up with

ways to eliminate the little free time he has left.

copyright © Charles Roberts 2002

This article first appeared on www.kenstone.net and is reprinted here

with permission.

All screen captures and

textual references are the property and trademark of their creators/owners/publishers.

|