By Loren Miller

For filmmakers who want to stretch their

skillsets, who need to build, not just composite imported

graphics, a range of excellent 3D programs exists for Macintosh

and Windows these days. Here I'd like to introduce three of my

favorites: Kinemac, SketchUp and Cinema 4D, which represent surface,

underwater and ocean bed of such applications. The contrast between

them may prove useful in deciding what's right for you.

The first program is closest kin to Apple's

Motion

3 - essentially a 3D animation/rendering package. The latter

two are broadly speaking MAR's- Modeling - Animation - Rendering

applications, which distinguish these from products like Motion

and After

Effects-- which don't support in-program modeling. But all

three programs discussed here allow you to build and move shapes

in three-dimensional space, dress them with texture, lighting,

surface reflectivity and shading. Depth illusion becomes compelling

when animated, as you orbit an object, move it or move past it

and watch the lighting and shadows change on surfaces as the

view changes.

Kinemac,

(for Macintosh only, www.kinemac.com

), is "3D for the rest of us." It's a $249.00

program which offers easy-to-build shape primitives and easy-to-plot

logo and package art fly-ins and orbits. It provides easy mapping

of preset textures and very cool surfaces such as shiny metal;

and which leverages underlying graphics technology on Mac OS

X. It supports PowerPC and new Intel Macs running OS X 10.4 or

later.

Kinemac provides an elegantly simple

interface for accurate rotation, positioning and scaling of objects,

and building useful graphics, like QuickTime movies pinned to

moving frames, or text mapped with reflective metal surfaces.

You can type text and then extrude it into 3D blocks.

Animation is dead simple and control

complexity is hidden until you need it. Just set a keyframe,

move the cursor down the timeline to a new point, rotate or zoom

the object or camera in relation to the object to set another,

and play it to review. You can manipulate the keyframes, control

acceleration of moves ("eases" or "feathers")

for smooth ins and outs using bezier controls.

Kinemac is handsome, productive, a lot

of fun to use and the results can be exported via QuickTime to

any other program accepting the format. The Help document is

clean and lean.

Google SketchUp

(for Macintosh and Windows, free version and Pro version, $495.00

from www.SketchUp.com)

is a "near-MAR"-- primarily an architect or designer's

fast rendering tool and becoming popular for quick film blocking

and scene previz. Originally from @Last Software out of Boulder,

CO and still run by them, Google acquired the product to enhance

Google Earth and offers an invitation to submit your own local

landmark 3D models using SketchUp. It's an excellent fit for

this purpose but offers much more. Now at version 6, this is

a rapid previz tool with fun modeling tools and simple page-based

walkthrough-style animation.

SketchUp is easy entry but getting richer

by the version. Using its patented drawing and inference system,

which you can acquire quickly from available video tutorials,

you can build a very nice looking house in minutes, by drawing

shapes, pulling and pushing surfaces into blocks, and creasing

surfaces to create separately-moveable areas. You can even simulate

an architect's rendering of your sketch-- and then walk through

it!

SketchUp's new Sandbox Tools offers limited

mesh editing of contours for more organic shapes. It gives you

control over global time-of-day lighting and cast shadows on

the fly. Unlike Kinemac, SketchUp is not keyframe-based but page-based

animation, which means: set a page, change your angle or view,

and set a new page. The program "tweens" pages to create

a smooth animation, but there are no eases or other controls

available, which can give animation a robotic, choppy look. Expect

this to be addressed in updates.

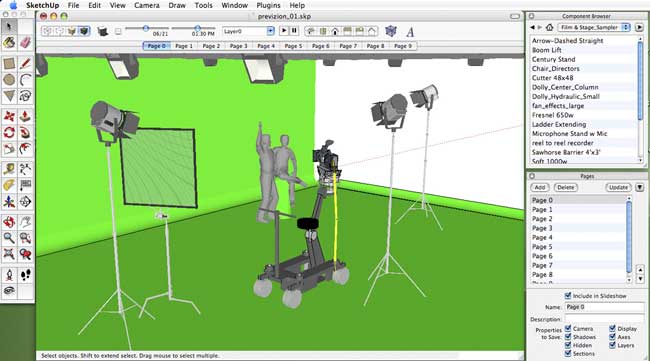

SketchUp offers a vast library of prebuilt

components in landscaping, architecture, and even a Film and

Stage library which allows you to plan production blocking of

scene locales using realistic articulated equipment which you

simply pop into a scene and arrange. Many components come with

moving joints grouped. For instance, just "explode"

a lighting unit to tilt the light head, then regroup to fix it

there. (Unfortunately you cannot generate a "real"

light source with beam control from such objects, as you can

in higher end products like Cinema 4D, discussed below.) I couldn't

find a classic Worral Geared Head so I built one (it's under

the camera in the illustration) eventually for their 3D Warehouse

-- a free emporium of components.

Video tutorials are available free online

and the online manual is excellent.

Maxon Cinema 4D

(for Macintosh, Windows, and Linux, www.maxon.net)

was developed in Germany in the early 90's, originally for Amiga

computers, and today represents a deeper level MAR with very

powerful modeling features, procedural (layered) surface editing,

kinematics (to simulate biomechanics such as walking, flying,

and sympathetic moving machine parts), richer lighting, camera

control and editing. C4D sports a spontaneously customizable

interface and ease of control over scene building and navigation.

Its nearest cross-platform competitors are Maya and Lightwave,

and the contest looks fierce. CD4 elevates 3D to an art and craft

from which you could really forge a career.

According to CEO Paul Babb, almost every

Hollywood film today contains production work done in C4D, from

the opening leaf scene in Spielberg's War of the Worlds to

effects in Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean. It's also

found in story previz-- the plotting of elaborate effects from

easily-changed wireframe or fast shaded rendering.

I first encountered C4D when it was bundled

with Final Cut Pro as a "Go" version, light and easy.

It has surely grown up five versions later and now at Release

10, reflects years of listening to artists and giving them formidable

controls for pro character, architectural and landscape creation

and animation. Maxon has worked hard to build a consistent and

integrated look and feel no matter which of its many tools and

modes are deployed.

C4D is used by Hollywood matte painters

for its paint tools (notably the Bodypaint 3D module, previously

separate), and by professional motion graphics artists who animate

characters, lighting, and even type, and need hassle-free integration

with compositing programs like After Effects, Combustion, and

Shake. In video work, C4D is popular for creation of virtual

sets-- composited with talent photographed against blue or green

screen stages. It excels at high end architectural and product

modeling and illumination. The character animation module, MOCCA,

is powerful. Animation is keyframe-based and offers complete

control over acceleration and velocity.

The C4D Core Package costs $695.00, includes

full modeling toolset, basic inverse kinematics and animation,

with several add-on modules available a la carte, or as part

of special bundles, such as the XL Bundle, which adds Thinking

Particles, MOCCA, and Advanced Rendering for $1995. A Studio

Bundle comes with everything available for C4D at $2995, adding

high-level features such as Hair construction and rendering;

professional animation physics such as IM and photorealistic

ray trace rendering.

Give C4D your time. It requires practice

to master its rich toolset but it's very logical. The enclosed

narrated video tutorial DVD really nails the basics, taking you

through the development of a fairly elaborate animated park scene.

It demonstrates organization and modeling; invisible "rigging"

of characters or objects for joint movement; customizing surface

treatments: wood grain, bumpy cast iron, eyeballs, flesh.

Both online and printed QuickStart manual

hold more beginner detail. There are a few annoying typos and

gaps in tutorial flow, and it's a little outdated regarding minor

interface changes. But there's also an online community of C4D

users who are very helpful to newbies.

So don't space out on 3D -- there's something

available for everybody!

Originally published in Imagine News,

www.imaginenews.com.

When he's not orbiting a 3D model of his dream

cutting room, Loren S. Miller is reporting, editing, producing

for venues like Digital Production Buzz, or consulting. Reach

him anytime at techpress@mindspring.com.