Introduction:

The Problem

This article describes an off-the-beaten-path workflow that arose

from wrestling with a common problem: bringing film, shot at

24 progressive frames per second, to digital video, which normally

runs at 29.97 interlaced frames per second--without losing the

progressive frames. If your finishing format is DVD or broadcast

tape, why would you need progressive frames? One reason is that

punching out mattes for visual effects compositing tends to be

a lot easier, and the mattes infinitely cleaner, when you have

full progressive frames rather than interlaced fields from separate

frames. Another is that you might not be finishing to NTSC--you

might print to film from video, a process that's rapidly becoming

more commonplace.

The standard Apple solution to

this problem is to use Cinema Tools to remove the 3:2 pulldown

introduced in the telecine process, thereby (we are told) restoring

the 24 progressive frames per second we started with. But that's

not how it tends to work out. Too often the pulldown removal

process leaves unwanted interlacing artifacts, seen as horizontal

lines in the areas of the frame where we should be seeing the

blur of a moving object.

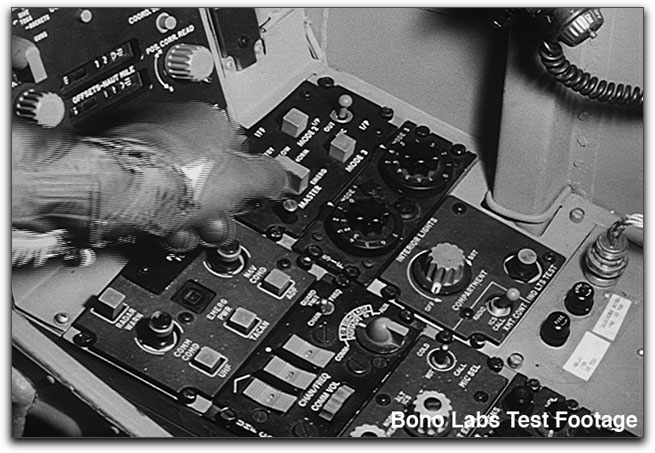

You can see the effect clearly

in the following two images. The first image is the result of

removing the 3:2 pulldown in Cinema Tools from a 24 fps clip

captured with a standard telecine process. After trying various

settings in Cinema Tools, such as changing the field order and

so forth, this image is the best I could do with Cinema Tools'

reverse telecine:

This second image is the same

frame. It is taken from the version of the footage that was transferred

at 30 fps with no pulldown, and then conformed to 23.98 fps in

Cinema Tools. If my job were to isolate the pilot's arm with

a mask, I'd much rather be working with this frame:

I've been unable thus far to get

a grip on just why Cinema Tools doesn't always cleanly remove

the pulldown (my guess is it may be getting the field order wrong

when it's compensating for the jitter frame), but the fact remains

that it does. I have heard this from numerous sources as well;

no one I've ever spoken to has gotten a clean 3:2 pulldown removal

from Cinema Tools using reverse telecine.

The Solution

While researching various labs and processes, I came across a

lab that does direct-to-drive transfers in HD and NTSC. The lab

is Bonolabs of Arlington, Virginia (http://www.bonolabs.com/tapeless.htm).

You ship them your negative, and they ship you a hard drive with

your footage on it in 24 fps progressive HD, or 29.97 fps NTSC

with a 3:2 pulldown added, or 30 fps with no pulldown. This last

option initially puzzled me, so when I requested their "test

drive," I asked them to include a 30 fps progressive clip.

The footage I received was 35mm

film transferred to 24 fps, 1080p 10-bit uncompressed 4:2:2.

There was a different film clip transferred as 8-bit uncompressed

4:2:2 NTSC with the 3:2 pulldown, so it ran at 29.97, and the

same clip transferred again with the same codec but transferred

at 30 frames per second with no pulldown. My suite isn't yet

HD capable, so the HD clip brought my dual-G5 FCP machine to

its knees as expected.

The NTSC clips, however, got my

attention. The clip transferred at 30 fps (but really running

at 29.97 fps, of course) showed faster motion in the frame than

the one transferred with the 3:2 pulldown, and it ran 15 seconds

shorter to boot, at 01:05 versus 01:20. After conferring with

the lab, I realized that this was deliberately done. 16mm or

35mm film is often transferred at 30 fps for broadcast, but this

has the unfortunate side effect of speeding up the action by

about 25%, and changing the pitch of the sound.

But Cinema Tools has a cure, at

least for the image side. There's a "conform" button

on the Cinema Tools main window that allows you to change the

frame rate of a clip without reprocessing the clip itself. So

by conforming the clip's speed from 29.97 fps to 23.98 fps (or

24 fps for that matter), Cinema Tools restores the clip's proper

speed and, therefore, its running time. It's the digital equivalent

of turning the switch on a projector from 30 fps down to 24 fps.

Once this is done, the sound, transferred separately at its proper

speed, can be re-synched to the picture in the edit. For someone

like me, who trained on a 16mm editing bench with a gang synchronizer

where synching is done with a film splicer and a permanent marker,

this is a cinch. But as always, your mileage may vary.

This process also allows for better

slow-motion effects if your originating medium is digital video.

For example, Panasonic's AG-DVX 100A doesn't shoot in progressive

modes faster than 30 fps. So we're stuck shooting 24p or 24p

Advanced and using time remapping in FCP or After Effects, and

living with interpolation problems. But if you shoot your slow-motion

footage in 30p mode and conform to 24 fps (or 23.98 fps), your

footage is now 25% slower to start with--so you have a leg up

on your time remapping.

The Process

The procedure is short and simple. Your clip should already be

in Quicktime format, in whatever codec the lab has used to create

the clip. In my case with Bonolabs, the footage arrived as Blackmagic

10-bit uncompressed 4:2:2 files at 30 fps progressive. I can't

say enough about how great the footage looked, even though it

was shot under very poor conditions with 7294 stock (remember,

this footage is 20 years old). As with the 35mm test shots, at

30 fps the motion looked just a hair fast. The sound was transferred

from its 16mm mag to digital files at 24 fps for synching later.

As a practical matter, I have tested this workflow from raw clip

through to DVD output, and it works well. Of course, as always,

YMMV.

WARNING:

This is a destructive process, meaning that Cinema Tools performs

the conform operation without presenting a "save as"

option. If you wish to retain an unconformed copy of your clip,

make a copy with a different name. You can do this in the Finder

by right-clicking the clip and selecting "Duplicate,"

or from within Quicktime Pro using either "Save As"

or "Export" (remembering not to recompress the clip

and to make the clip self-contained).

Having taken the proper precautions,

now we're ready:

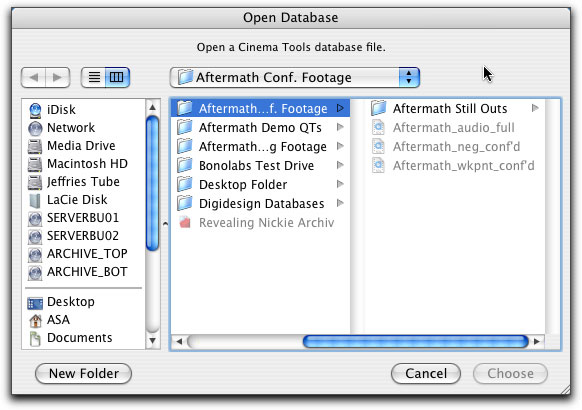

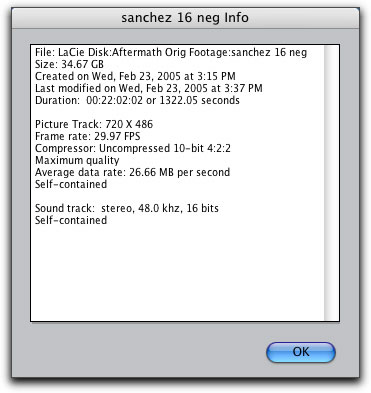

1.

Open Cinema Tools. Cinema Tools will present an Open File dialog

asking you for a Cinema Tools Database file. Click Cancel to

close it.

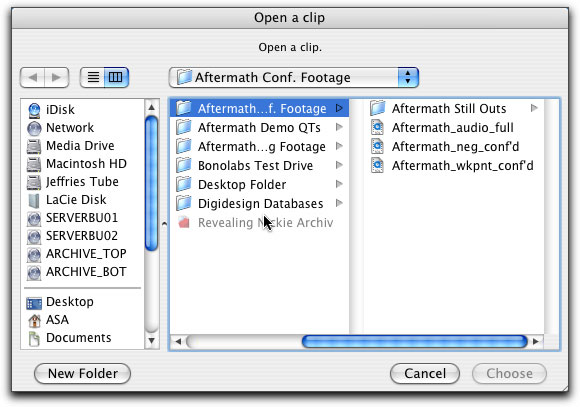

2.

Load your clip. The command is File--> Open Clip. The "Open

a clip" dialog will come up. Select your clip and click

Choose.

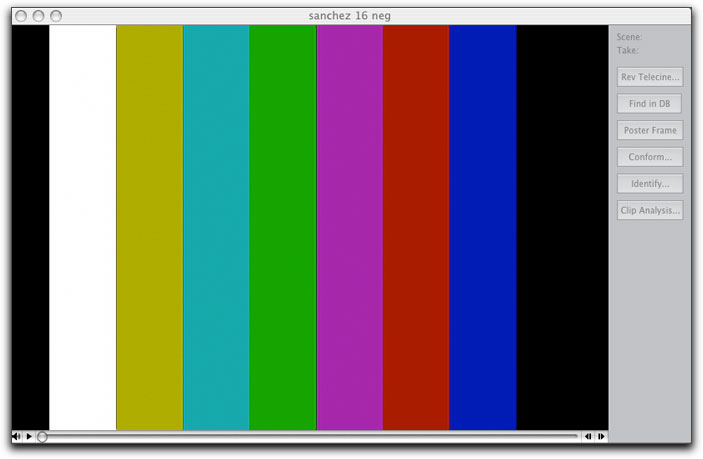

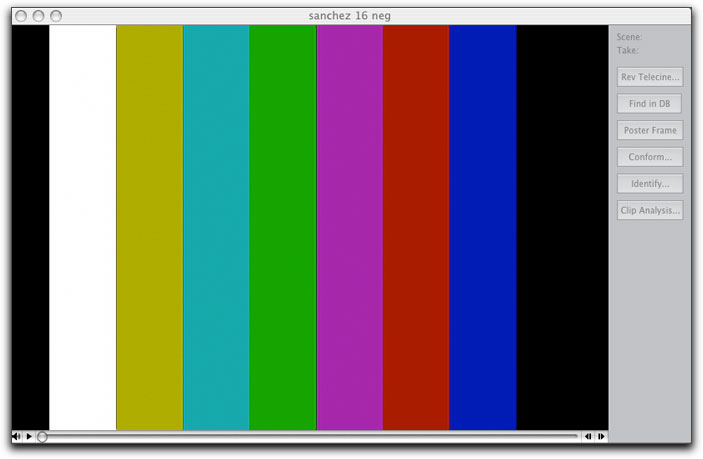

3.

The Cinema Tools main window will open with your clip loaded.

On the right side of the window are several buttons: "Rev

Telecine" (for removing pulldown or "reverse telecine"),

"find in DB" (grayed out in this case), "Poster

Frame," "Conform," "Identify," and "Clip

Analysis." Clip analysis brings up your clip's information

for reference. Here, we see the frame rate is NTSC 29.97 fps.

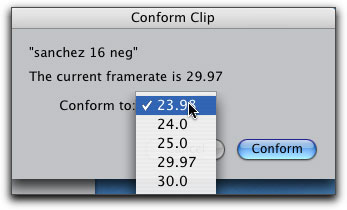

4.

Click on the "Conform" button. A dialog box will come

up. Here, it informs us the clip's current frame rate is 29.97

fps (as we learned from looking at the clip analysis). We select

23.98. We could select 24 fps exactly, but in my case, I preview

NTSC video via Firewire. This requires that the frame rate be

23.98, since Final Cut Pro won't output real-time 24 fps monitoring

via Firewire. In any event, 23.98 is suitable even for film-out.

Bottom line, I use 23.98 fps and everything works fine. Choose

your frame rate and click "Conform" to execute.

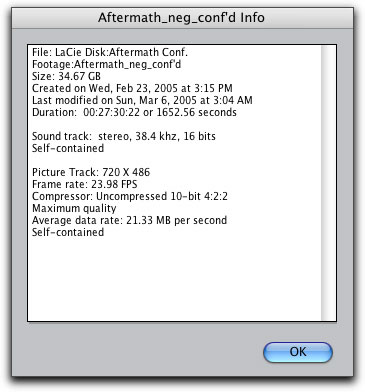

5.

You'll hear a very short read-write on your hard drive. Cinema

Tools is not reprocessing the entire clip, but rather re-writing

the frame rate info. So the process takes less than a second

to complete, and you may not even realize it's done. But take

another look at the Clip Analysis dialog to see your clip is

now 23.98 fps.

6.

Close Cinema Tools. You're done. Your clip will now import into

Final Cut Pro at 23.98 fps. If you have a sound track, load that

into FCP and sych by hand. In my case, the sound track synched

on the first try. The total film is about 6 minutes long, and

I encountered no drift at all between the sound and picture.

In a very long clip, you might see some drift-but chances are

you'll be dealing with many short clips, not one enormous one.

A final note on how the lab may

deliver your footage. In this case, Bonolabs decided it was more

economical to spool all of my negative, nearly 1000 feet, onto

a single reel and transfer it all into a single video clip on

the hard drive. This means cutting the individual takes apart

by hand in FCP. You can use the razor tool, or just set in- and

out-points in the Viewer before you drop a take into your timeline.

You may be able to negotiate with

your lab to give you a transfer "flash to flash," meaning

the telecine process will give you individual clips between flash

frames on your negative. A flash frame results whenever the filim

camera starts and stops. As the camera motor speeds up on startup

and slows down to stop, the lower speed of the motor results

in longer exposures on one or two frames known as "flash

frames." When you're spooling through a reel of film, looking

for flash frames is a quick way to spot where a take begins and

ends.

Of course, there are other methods

available. Some labs may offer 24 fps progressive transfer of

your film at NTSC resolutions, in which case this process is

unnecessary (unless of course you want to conform your 24 fps

clips to 23.98). If you're working in High Def, 24 fps progressive

transfers are more common. But in this case, I found the 30 fps

NTSC direct-to-drive transfer the most economical solution. For

such instances, the availability of the Conform command in Cinema

Tools gives us a viable workflow at lower cost.

All things being equal, I'm a

big fan of lower cost.

Aureliano Sanchez-Arango left the practice of entertainment law to form his own production

company, Me & The Wife Productions, LLC, and is a founding

member of InDVFX Enterprises, LLC, bringing high-end visual effects

to the independent filmmaker. Direct inquiries to info@meandthewife.com.

copyright ©

Aureliano Sanchez-Arango 2005

This article

first appeared on www.kenstone.net and is reprinted here

with permission.

All screen captures and

textual references are the property and trademark of their creators/owners/publishers.