|

|

| Tutorial: -Working

with BWF Audio in FCP |

March, 2006

Working

with BWF Audio in FCP

by Clay Coleman

If you haven't been confronted with it previously,

.BWF (Broadcast Wave Format) is an audio format initially

developed under the auspices of the European Broadcast Union

around 1996 as a non-proprietary 24 Bit Integer audio file format.

The original intent was to provide broadcasters within the EBU

with a simple, high-quality, tapeless digital audio platform

to streamline workflows for the member countries. Since adding

TimeCode and MetaData functionality in 2000, it has become a

widely-used format for hard-disk digital audio recording for

radio, television and film. Using a BWF recorder, like the Sound Devices 744T, and a simple file conversion

tool, the BWF2XML file converter, BWF allows for extemely fast

audio capture in excellent quality with multiple tracks simultaneously,

and while retaining original timecode and filenames for later

synch to picture and audio post workflows.

Interesting thing is, BWF was made QuickTime

compatible somewhere around 2002, but for whatever reason, that

fact never made it into the FCP or QuickTime documentation. BWF

audio is still not mentioned in the FCP Studio manual (as of

2006), and that is something Apple should definetly change in

future versions. In fact, if you had a version update request

something along the lines of "hey, how about giving us really

good digital audio with instant multi-track import and with original

timecode, and in PAL, NTSC, and 24, and how about with a simple

way to maintain shot, scene and take numbers, and please make

the workflow completely tapeless, etc., etc.", well, wait

no longer. It already exists. Those in the know have been using

BWF for some time now. I came across it recently when a recordist

on a recent job sent me his workflow specs. After then posting

a query on the lafcpug forum, I was clued in pretty quickly.

The rest was a bit of research, a few tests, and then using it

on the current job. Thus the impetus for this beginner's how

2, and in hopes that BWF audio comes into much wider use, because

it's an editor's dream.

The Gear:

This is the Sound Devices 744T deck,

as was used during shooting. Up to four tracks of BWF audio can

be recorded to it's internal 40 GB drive simultaneously. How

much audio (in hours and minutes) you can get onto the drive

of course depends on the settings used. The chart below from

the Sound Devices homepage gives you the general idea of storage

requirements for one track of audio at the various settings availalbe.

For example, recording at 24 Bit / 48K, the 744T would allow

you about 20 hours of 4-Track audio. More than ample for a day's

shooting.

On the 744T's right side panel, you'll

notice the Firewire 400 port. It's both Mac and PC compatible

(OSX), and allows connection directly to your computer. The 744T's

internal disk mounts as an external drive on the desktop, letting

you copy BWF files straight from the deck to your media drive.

For editors though, one of this deck's

handiest features is the ability to enter individual filenames

of up to 9 Digits. For example, we opted for a standard scence,

shot and take number routine, thus allowing for filenames like

03-07a-5 (Scene 3, Shot 7a, Take 5) as per the director's breakdown,

and as subsequently slated. Once set, those filenames are maintained

from recording all the way through edit and post. A major time-saver,

streamlining the otherwise tedious job of logging and capturing

audio down to a few mouse-clicks.

Getting .BWF Files in:

Step one

in importing and converting .BWF audio is to get the orignal

files copied to a designated media drive on your machine. As

above, you can pull it right off the deck via Firewire, but in

most workflows, you won't have (or even need) the deck in the

edit bay to import from. More likely, you'll get the material

from the audio dept in the .BWF file format. In this particulart

case, I was given a Data DVD with all the audio files, so bringing

it in was just a matter of drag and drop. Folders were created

for each shoot day, a procedure to retain as will become evident,

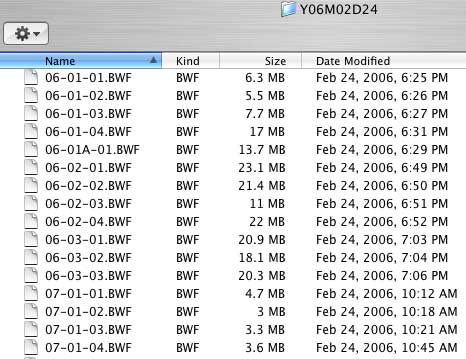

and saved to the project's media drive. Popping open a folder

as below, you'll see the individual file names appear with the.BWF

suffix, file size, and date modified info. As advertised, each

audio take is displayed as the recordist named it during shooting

by scene, shot and take numbers.

|

Original folders:

|

Sample contents:

|

Converting and Saving the Files via

BWF2XML:

Step 2:

to start the conversion process, you need to purchase and install

the BWF2XML

tool. Details on how to do that are at the end of this

article. Once in your applications folder, the converter icon

shows up as below. Double-click to launch.

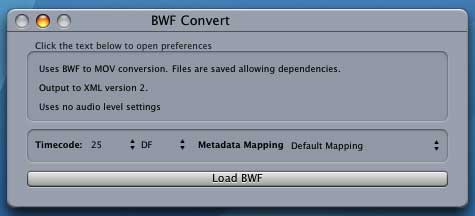

You then get the BWF conversion dialog

window:

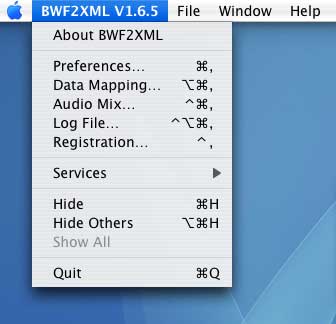

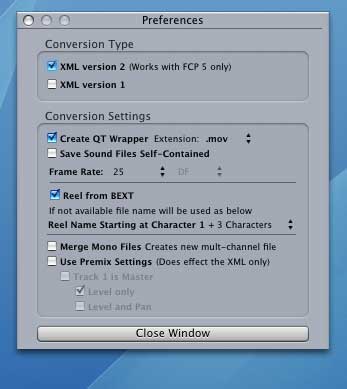

At this point there are 2 choices, either

hit the Load BWF bar to proceed with the conversion at the current

settings, or go into preferences to fine tune things. Prefs are

accessed by simply clicking in the text area (which opens an

additional preferences pane) and by heading up to the menu bar

and adjusting further settings there.

A number of very useful features are

available, including being able to generate a log file. A 12

channel audio mixer let's you make volume and pan adjustments

prior to conversion. (Hang on, twelve channels? Yes, but for

the moment, just to keep things simple, I'm sticking with up

to 4. More on multichannel towards the end of this piece.) Video

frame rates of 23.98, 24, 25, 29.97 and 30 fps are supported,

as well as the more exotic 29.97 DF vs. NDF issues which can

arise when synching 29.97 audio to telecine. A word on that later

too.

|

|

It would take too long to go into all

the details of each setting here, but suffice it to say that

after testing the main functions, everything works as it should,

and the Help documentation is simple and straightforward. To

convert the files at hand, I set the timecode to 25 (my timebase

is DVCProHD/1080i50), hit the "Load BWF" bar, set a

destination folder, and started a batch conversion of each shoot

day's files (yes, you have the option of grabbing individual

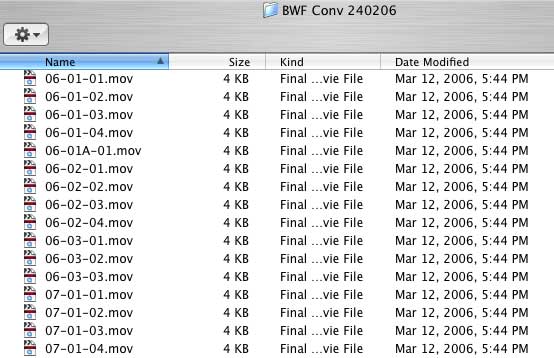

files or an entire batch). The converted files in one of the

new folders (each folder was named BWF Conv plus date), look

like this:

The first thing you'll notice is the

very small and continuous (4KB) file-size displayed for each

take. That is because although they are defined as FinalCutPro

Movie Files, they are actually links between the BWF format and

QuickTime via an XML file that is generated during conversion.

The XML file enables retention of each files' MetaData, keeps

the tracks separate, and an XML file for each conversion is saved

to the destination folder.

Important: this is where you've got to

exercise some caution, because once converted, these file links

can now be imported into FCP and edited and played back just

like any other audio files, but, they can't be moved from the

their current location without potentially becoming corrupted.

They also can't be copied to a different drive for the same reason.

However, there is an easy fix to that problem, which I'll get

to in a second.

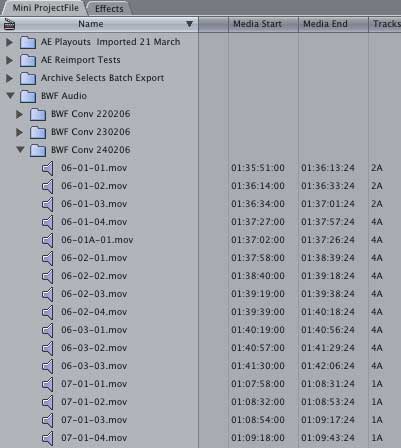

Importing into FCP:

Step 3:

to get the converted audio into FCP, just import files or a folder

as required in the usual manner. In the FCP browser, each file

shows up with the original scene, shot and take number, with

the original timecode, and displaying how many tracks each file

includes:

As to be expected, when opening a clip

in the viewer and with the playhead set at the head as below,

you then see each track within the clip, the audio waveforms,

duration, original timecode and original filename. Very, very

cool.

From there, it's just a matter of getting

onto the timeline to synch to picture. In this case we did it

the old way, lining up slates with waveform peaks. If you have

timecode from camera into the BWF recorder (which the 744T can

do), then of course you'd have the added luxury of simply lining

it up by TC. Here's a few 4-Track clips, recorded with various

boom and radio mics, after editing into the timeline for synch

to slates:

Backing Up to QuickTime:

The only other thing you really should

do is Batch Export those converted files from the browser as

QuickTime .mov files with Audio Only. Edit with those, and keep

the original .BWF's and the 4KB converted files as backup. You

can then move the new QT .mov files around to other drives if

need be without them becoming corrupted. And yes, the exports

do retain all the separate tracks, the original filenames, and

the original TC, so there's no reason not to take the safe route.

At this point you're probably wondering

what happens if you open a .BWF file with QuickTime or Compressor

without doing the conversion. QuickTime is .BWF compatible, so

you can hear the audio in the QT player, and you can export to

.mov or .aiff. Only thing is, it's then maximum 2-Track and you

lose the original TC. If you import a .BWF file into FCP directly,

it will display all the tracks and you can playback and edit

the clip, but again, the original TC is gone, and any attempts

to export starts creating a lot of error messages. Therefore,

the BWF2XML tool is essential to making the workflow run smoothly

and with all functionality fully operative.

Bottom Line:

And that's basically it. Although the

workflow via XML and then to QuickTime involves an extra step

or two, the conversion goes so quickly that it doesn't really

matter. In this case, audio from a four day studio shoot amounted

to just over 300 takes, or about 3.2GB. The initial conversion

via the BWF2XML tool went off within two minutes. Importing into

FCP and then Batch Export to QuickTime took about 4 minutes on

a dual 2.5 G5. Not an issue, especially when compared to capturing

DAT audio real-time, or having to make second passes of camera

audio in real-time to get all the tracks, plus the logging hassle.

A bit of good file organization is all that is otherwise required.

Another added benefit of backing up to

QuickTime from the converted files, is that one can of course

send the audio to a Soundtrack multitrack project, or export

to .omf for further sweetening and mix at an audio facility.

There are numerous very good reasons for using external audio

both for film and video, the main one being that the camera is

often nowhere near where mics want to be, thus involving extra

cables and gear hanging off the camera for people to stumble

over and fumble with, which DP's generally despise. The recording

quality depends largely of course on the skill of the recordist

and the mics used, but in the hands of a competent person, .BWF

is an excellent low-cost high-end solution. Also for the editor,

who, with literally just a few mouse clicks, is spending less

time on the drudgery of log and capture and more time on the

important part.

The Bigger Picture:

As regards 5.1 and 7.1 recording, editing,

and mixing is concerned, .BWF is already in use in that arena

too, and that's the reason why the conversion tool currently

has a 12 channel mixer on board. A .BWF file can contain 12 or

more tracks of 24 Bit audio. Theoretically, the number of tracks

is unlimited. It's currently a hardware issue to handle that

much throughput to disk, but the format can already deal with

it. On a multi-camera shoot, 12 or more channels of audio is

not uncommon. In the future, we'll be seeing machines that can

record multiple tracks, while saving to one multi-channel .BWF

file. Therefore, although video has taken the limelight recently

with the jump to HD, the audio world has not been asleep at the

switch. Far from it. Great new possiblities are already here

with more to come in the very near term.

The .BWF file format is certainly something

FCP users need to at least know about. Imagine working in DVCProHD

on P2 with .BWF 24 Bit external audio. No tape, no decks, modest

file sizes, no expensive storage solutions, excellent qualtiy,

and instant compatibilty with all the FCP Studio apps. A true

tapeless post solution. Let's get all that into the FCP Studio

Manual.

Contributors:

Many thanks to Andreas Kiel at

Spherico.com,

the rocket scientist who developed the BWF2XML tool. Available

for $95 in the lafcpug store, it's very fairly priced,

especially when you consider the time-savings involved. Andreas

also provides support for various film and video workflow solutions,

and is experienced in dealing with longform projects as well.

Should you get stuck with 29.97 DF/NDF audio synch to telecine

problems, the converter can handle it. Andreas can tell you how.

Contact him directly too for any customizing needs.

Thanks also to David Urban, the

recordist on this job, who gave me a few test files to play around

with prior to shoot, then generally explained how it all works

and took me through the converson procedure first time around.

Very helpful.

Further thanks to Jon Tatooles,

one of the founders at Sound Devices. Their 744T is a great

piece of gear, very innovative, easy to get into, very robustly

built for field use, and thus highly recommended. The ability

to enter scene, shot and take numbers as individual filenames,

and thus retain that information all the way through post, is

an excellent feature.

Resources:

Want more tech? The following links will

get you started:

The European Broadcast Union's .BWF spec

page with Userguide and FAQ:

www.ebu.ch/en/technical/publications/userguides/bwf_user_guide.php

Sound Devices Homepage with Gear, Descriptions,

Specs, and PDF's

www.sounddevices.com

The BWF2XML conversion tool Developer's

Homepage:

www.spherico.com

Hope this helps,

Clay Coleman

Oasys Editing

Munich

All images used by permission.

/ © 2006 Clay Coleman

Clay

Coleman is a free-lance FCP editor since version 2.0. Oasys

Editing is his home base in Munich. Projects there include work

for TV, Corporates, Short Features, and Docus. Clay also teaches

DV filmmaking at Munich's Graphic Arts Akademie U5.

|